For all the campaigning and schmoozing members of Congress have to do, the truth is that the vast majority of Americans will never actually meet their lawmakers.

To be fair, not everyone wants to. But among those who do, there's serious competition for a lawmaker's time. So, how does an average citizen get access on Capitol Hill? The quick answer: It's not easy.

First, do the math. When it comes to face time with a member of Congress, there are 535 of them, and 314 million of you.

You can certainly try calling your congressperson's office to set up an appointment — or, you can take it a step further.

One Strategy: Hiring Someone Else To Hit The Phones For You

There are actually businesses in D.C. with one primary mission — to get you in the door of a lawmaker's office. Soapbox Consulting is one of them. It isn't a lobbying firm. It doesn't argue issues for its clients. It doesn't flash money around. What it does is get you face time by hitting the phones hard.

Kevin Schultze, who oversees scheduling at Soapbox, says it can take weeks, going back and forth at least six times to get on the calendar with a congressional office. And you have to fight to get heard through the din.

"There are so many requests on the desks of these schedulers, they tell us, that anything we can do to slow that down or to perk up their ears, we will use it," Schultze says. "The first thing we always lead with is the address, to show that that person is a constituent. But we have used information like, 'This person is a cousin of the congressman's,' 'This person went to high school with the congressman,' 'This person lived in the same dorm as the congressman.' "

Sometimes it means throwing whatever you can at the wall to see what sticks.

At one point, while Schultze is on hold with the office of California Republican Rep. Darrell Issa trying to schedule a meeting for a client, he gets a sudden inspiration.

"Congressman Issa provided a tour to their family last year," Schultze whispers. "So that's also one of the things that we would use to tell the scheduler that this person has a relationship with Congressman Issa."

Does this work? Soapbox can get you into a lawmaker's office, but most of the meetings it lands are with staff members, not with the lawmakers themselves.

That's fine for Soapbox's main clientele — advocacy groups that want to hit dozens of congressional offices on one specific lobby day. A coordinated visit like that can cost a few thousand dollars with Soapbox.

It's not cheap, but if access is what someone wants, he may want to spend even more, by donating directly to a lawmaker's campaign. Two political science graduate students recently found that might work a lot better.

Another Strategy: Donating Directly To A Campaign

David Broockman of the University of California, Berkeley, Joshua Kalla of Yale University and a liberal group called CREDO Action teamed up to conduct a little experiment last summer.

What they wanted to do was examine to what extent legislators take meetings with donors precisely because they've donated.

They sent emails to 191 members of Congress asking for a meeting to discuss a chemical-banning bill. All the messages were identical, except for two words: One email template asked the lawmaker to meet with "local campaign donors"; the other asked the lawmaker to meet with "local constituents."

"The offices who just thought they were being asked to meet with normal constituents, we almost never got a meeting with a member of Congress, or a chief of staff or a legislative director — the most powerful people in congressional offices," says Broockman. "On the other hand, when we reveal that the attendees were donors, they were more than three times as likely to get those meetings."

There are some caveats to point out: An office might have perceived a "donor" as someone who was more engaged in the community and would understand the issues better. Also, some offices might have automatically assigned higher-level staff to meetings with donors to ensure campaign finance rules were followed.

And the study doesn't answer this question: Even if donors were getting in the door more often, were they getting the results they wanted? Recent reports suggest that might cost even more money.

Results After Access: Spending Even More Money

Bill Ackman is a political donor who seems to be getting results. He's a hedge fund manager who bet a billion dollars on the demise of a nutritional supplement company called Herbalife. And to take the company down, his hedge fund Pershing Square Capital Management spent $264,000 lobbying last year, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

He also donated more than $32,000 to the general campaign fund of Senate Democrats. On a March 11 webcast responding to a New York Times story about his offensive, Ackman described the access he got on Capitol Hill.

"Beginning in the summer of 2013, myself and a few colleagues went down to Washington, D.C., to meet with senators and congressmen that our political advisers thought might be interested in our concerns about Herbalife," said Ackman.

The spokesperson for Democrat Linda Sanchez of California told NPR the congresswoman met personally with Ackman, and Ackman says he got an entire hour in the office of Democratic Sen. Ed Markey of Massachusetts to meet with key staffers who investigate big business.

Ackman says he has never donated individually to either member, but both of them did end up writing letters to the Federal Trade Commission to demand an investigation of Herbalife.

And the FTC opened a probe into the company just this month, Herbalife disclosed.

Sheila Krumholz of the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics says maybe you can't prove money is the singular reason Ackman got these results, but there's no question it set him apart on Capitol Hill.

"People who have deep pockets get special treatment; they get the kid gloves, because parties and candidates want to be able to enlist their support and count on them for financial support in the future," Krumholz says.

'Chipping At The Iceberg'

Meanwhile, people who don't have serious money often can't even get past the front couch of a lawmaker's office.

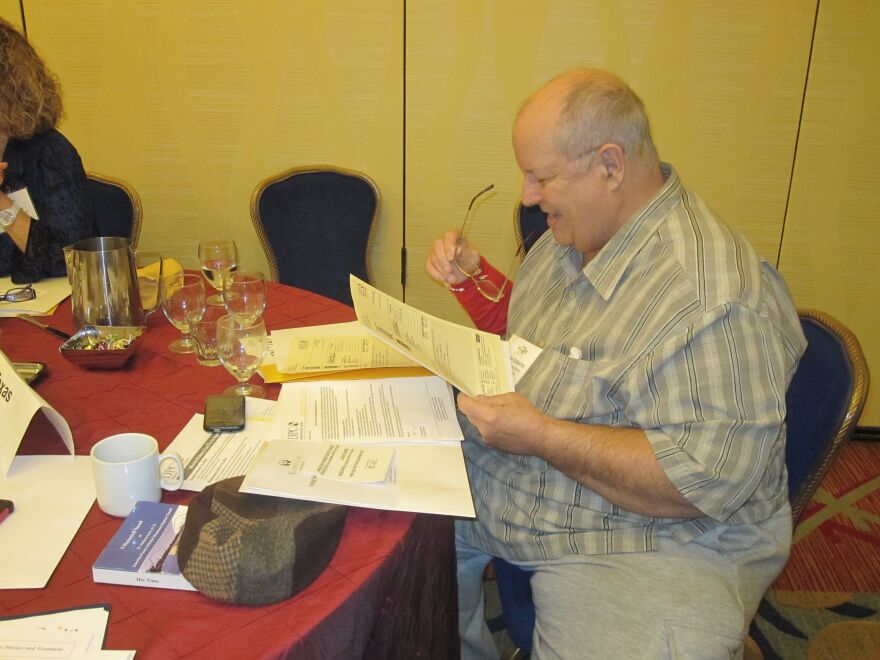

Devon Osborne is a dialysis patient from Dallas who got a meeting with two junior staffers in the office of Texas Sen. John Cornyn. Osborne is here with a group called Dialysis Patient Citizens, a client of Soapbox Consulting.

Osborne folds up his wheelchair, eases himself down with a cane on to a couch near the front door of Cornyn's office. He has 15 minutes to make the case for better Medicare coverage of kidney dialysis. And the staffers inform him that one of them might have to leave a few minutes early.

It was an ordeal for Osborne to come to Capitol Hill. It meant flying in early to get into a dialysis center at 4 a.m. Still, he says, these precious 15 minutes even with a junior staffer are worth the effort.

"It's chipping at the iceberg," says Osborne. "You know, this is the second or third time I've met with her, and each time it gets a little bit more familiar, and we get our point across each time."

This is actually Osborne's fourth trip to the Hill overall, and he says he has yet to land a meeting with his own congressman.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.